In January 1917, less than one month before the Interstate Bridge across the Columbia River was dedicated, the Washington State chapters of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) and Sons of the American Revolution (SAR) gave a water fountain to the City of Vancouver in commemoration of the Oregon Trail (Columbian 30 Jan. 1917:1). However, this was no ordinary water fountain: it was a large sculpture designed by the noted artist Alonzo Victor Lewis (1886–1946) (Poyner 2020). A DAR publication from April 1917 described the composition and construction of the fountain:

“Alonzo Victor Lewis, sculptor, of Tacoma, designed and supervised the execution of the fountain. It is interesting to know that Mr. Lewis is of the same family as Merriwether Lewis, of the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1803. The sculptor is descended from Fielding Lewis, who was brother to John Lewis, father of the pathfinder.

The fountain is of Tenino granite in three sections. The tall center shaft is polished and bears a tablet of golden bronze, depicting ‘The Spirit of the Trail.’ A beautiful allegoric figure typifying courage and hardihood, guiding the train of emigrant prairie schooners through valleys and forests to the land of the setting sun. The inscription at the top is ‘To the Memory of the Pioneers of the Oregon Trail, 1844.’ Insignia of the S. A. R. and D. A. R. in each lower corner of the tablet.

Below, cut into the granite and bronzed, is the title of the tablet and legend:

‘SPIRIT OF THE TRAIL’

Erected by

The D. A. R. and the S. A. R. in the State of Washington, 1916.

On either side of the center granite is a shorter shaft of smooth cut granite, ornamented with two large buffalo skulls in bronze, which bear a bubbling fountain drinking cup on each of the four horns. Below the skull, the bronze is so designed that a bucket may be hung to catch the flow of water. This will be useful to teamsters and chauffeurs. At the base is a stone trough of running water, where dogs drink.” (Daughters of the American Revolution 1917:1082-1083)

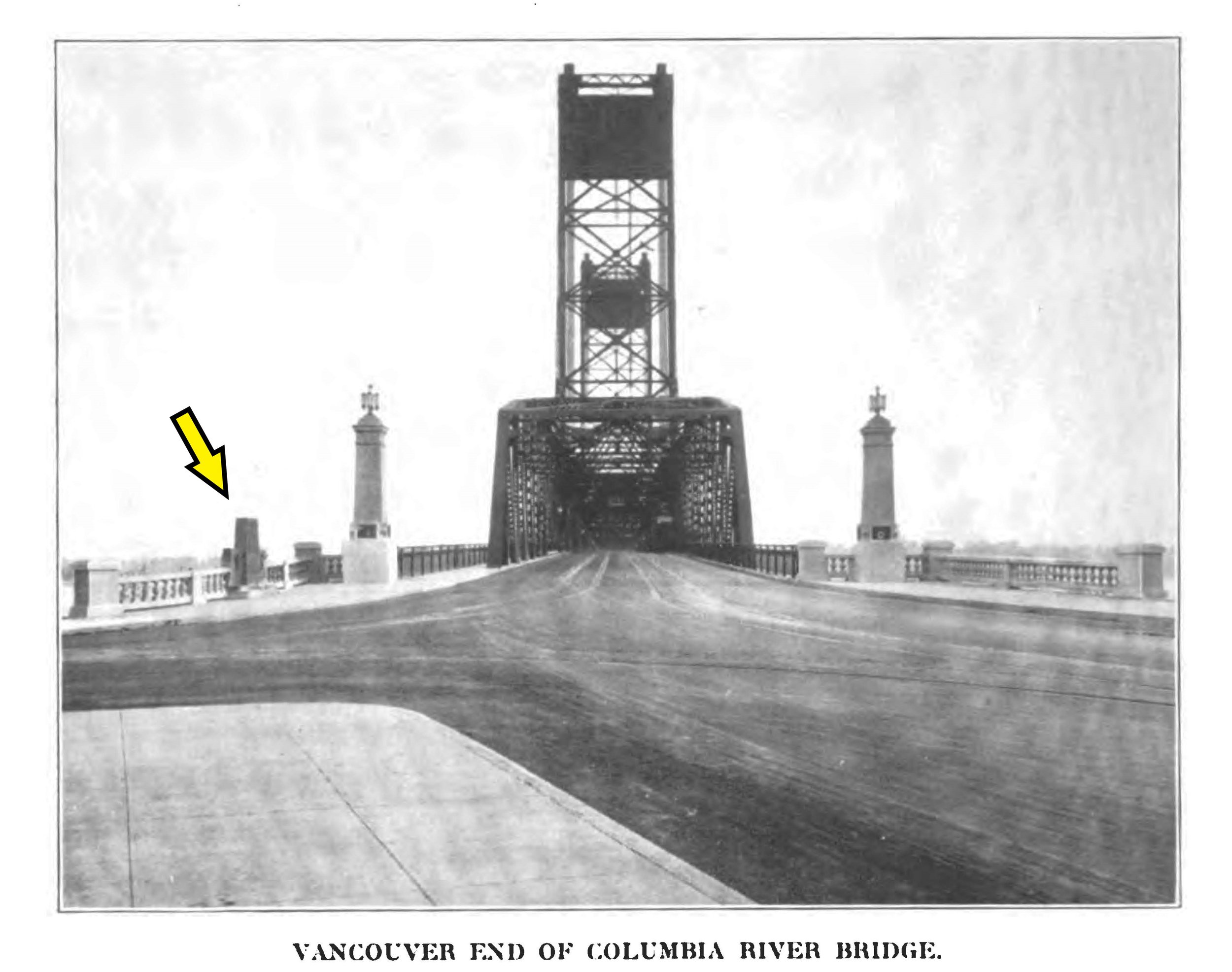

Historic photograph from Final Report: The Columbia River Interstate Bridge, Vancouver, Washington, to Portland, Oregon, for Multnomah County, Oregon, Clarke [sic] County, Washington.

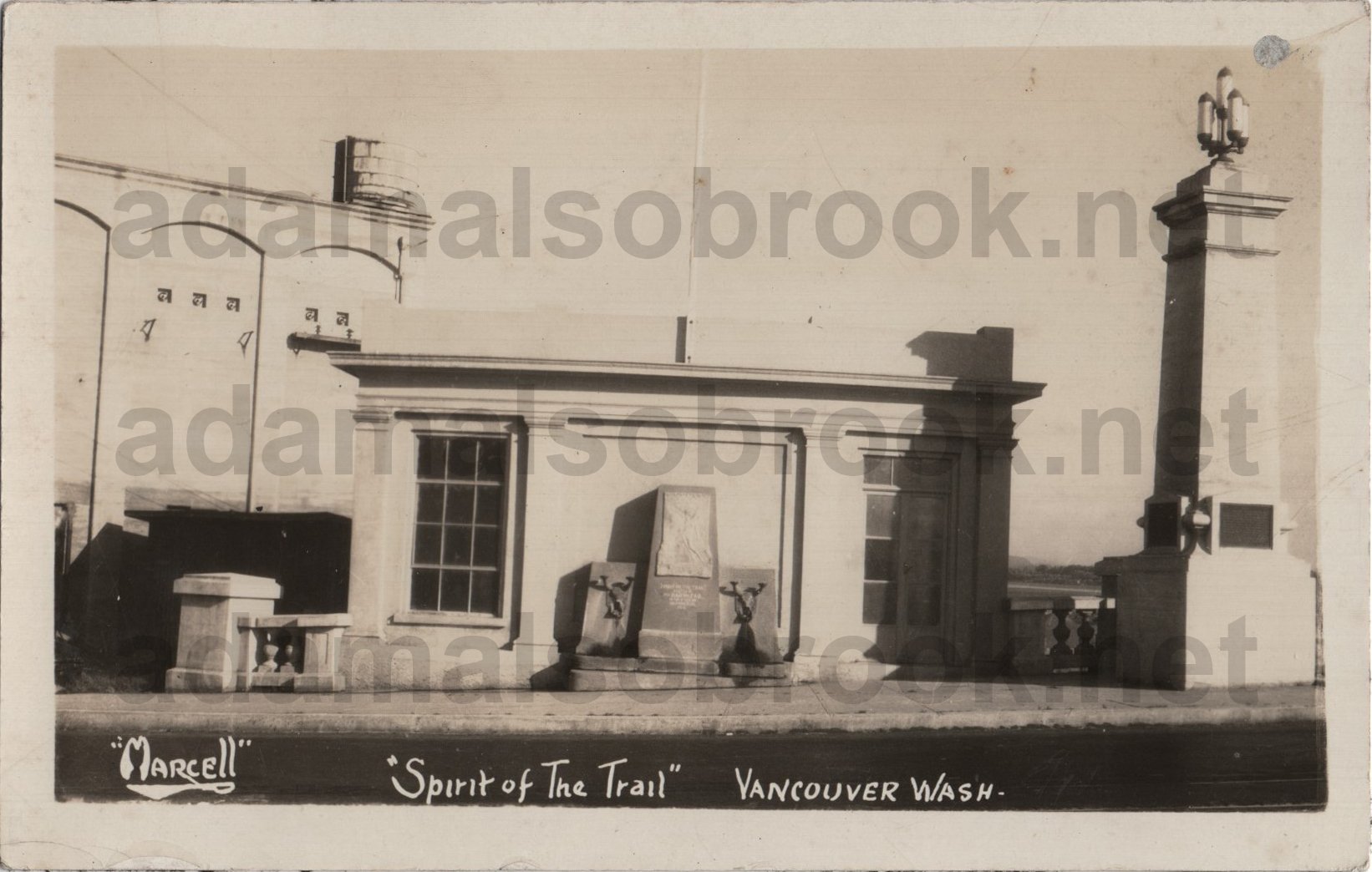

Workers installed the commemorative fountain approximately 50 feet north of the north portal of the Interstate Bridge. A very early historic photograph of the Interstate Bridge shows the original configuration of the fountain as it was installed, integrated into the concrete balustrade along the east side of the approach (Columbian 30 Jan. 1917:1; Harrington and Howard 1918:12). A one-story building for the bridge superintendent was constructed immediately behind the fountain in 1918, and this building served as a backdrop for “The Spirit of the Trail” until the building was demolished between 1959 and 1963. Another historic photograph taken by the Vancouver photographer Marcus Belmont Marcell (1869–1939) taken circa 1925 shows the configuration of the fountain in conjunction with the bridge superintendent’s office building (Alsobrook 2023:4).

Real photograph postcard (RPPC), circa 1925. This image shows the “Spirit of the Trail” at the north end of the Interstate Bridge at Vancouver, Clark County, Washington (Author’s Collection)

By the time the second Interstate Bridge was opened in 1958, the bridge approaches adjacent to the fountain had been extensively reconstructed. With easy pedestrian access virtually eliminated, by the early 1960s the fountain was practically forgotten. In March 1961, two articles in the Columbian newspaper reported on the forlorn state of the monument. The first article mentioned that the Fort Vancouver Historical Society repeatedly asked the Washington State Highway Department to move the fountain, but the state agency reportedly rebuffed the requests, citing lack of funding for the relocation project. The second article reported on initial efforts to raise funds for a potential relocation of the monument (Columbian 13 Mar. 1961:9; 15 Mar. 1961:20). By November 1961, the highway authorities relented, and it was announced that “The Spirit of the Trail” would be relocated to the Washington State tourist information center, an ersatz pioneer log cabin building formerly located east of the Vancouver Freeway (present-day Interstate 5) just south of what is now Evergreen Boulevard (Columbian 3 Nov. 1961:5). The monument was relocated to the tourist information center in April 1962 (Columbian 4 Apr. 1962:9, 11 Apr. 1962:2, 13 Apr. 1962:3).

When Interstate 5 through Vancouver was widened and reconfigured during the early 1980s, the 1950s-era tourist information center was removed, and a new rest area and tourist information center was constructed east of the interstate just north of Mill Plain Boulevard. “The Spirit of the Trail” was not included in the new facility, so the monument was dismantled and taken to a Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) storage yard at Battle Ground, Washington (Columbian 27 Jan. 1983:31). The monument remained forgotten at the WSDOT storage yard until 1999, when the Fort Vancouver chapter of the DAR tracked it down and announced their intention to rescue the sculpture from obscurity and return it to a public place (Columbian 3 Oct. 1999:13, 3 Oct. 1999:18).

By 2011, the DAR successfully relocated “The Spirit of the Trail”. The sculpture is now located adjacent to the Covington House, located at 4008 Main Street, Vancouver, WA 98663. The monument was rededicated in 2016 (Columbian 7 Sep. 2016).

WORKS CITED

Alsobrook, Adam

2023 “Interstate Bridge Transformer House / Portland Electric Power Company (PEPCO) Substation / Clark County Utility Substation.” Interstate Bridge Replacement Program, Section 106 Documentation Form (Individual Properties). ODOT Key No. 21570, WSDOT Work Order No. 400519A. Prepared by WillametteCRA.

Columbian (Vancouver, WA)

1917 “Beautiful Fountain is Given City.” 30 January:1.

1961 “Pioneer Monument is Going Unnoticed.” 13 March:9.

1961 “Move for Monument Long-Term Project.” 15 March:20.

1961 “Monument Move Given State OK.” 3 November:5.

1962 “Historical Marker To Be Moved Soon.” 4 April:9.

1962 “Marker Of ‘Trail End’ Is Moved. 11 April:2.

1962 “Trail’s End Moved.” 13 April:3.

1983 “It’s hard to hide an 8-foot monument.” 27 January:31.

1999 “History marker languishes in Battle Ground storage.” 3 October:13.

1999 “Marker.” 3 October:18.

2016 “Daughters of the American Revolution rededicate Oregon Trail plaque.” 7 September.

Daughters of the American Revolution

1917 Proceedings of the Twenty-sixth Continental Congress of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Washington, DC: Capital Publishers, Inc.

Harrington, John Lyle, and Ernest E. Howard

1918 Final Report: The Columbia River Interstate Bridge, Vancouver, Washington, to Portland, Oregon, for Multnomah County, Oregon, Clarke [sic] County, Washington. Kansas City, MO: John Lyle Harrington and Ernest E. Howard, Consulting Engineers.

Poyner, Fred

2020 “Lewis, Alonzo Victor (1886–1946).” HistoryLink.org Essay 20974. Electronic resource, https://www.historylink.org/file/20974, accessed October 3, 2023.